Anti-Bribery Laws in Australia

08 March 2022

This guide provides an overview of the Australian law relating to bribery and corruption, including bribery of foreign officials, and some practical tips to manage associated risks.

Topics covered include:

Introduction

In a world where business is conducted across national boundaries, foreign bribery and corruption is increasingly in the spotlight. More countries, including Australia, are becoming increasingly active in investigating suspected bribery both within and outside their borders and bringing enforcement action. Organisations need to be conscious of anti-bribery legislation, have policies and procedures in place to comply with that legislation and take steps to ensure that compliance is embedded within the organisation’s culture.

Generally speaking, bribery is the offer, payment or provision of a benefit to someone to influence the performance of a person’s duty and/or to encourage misuse of his or her authority.

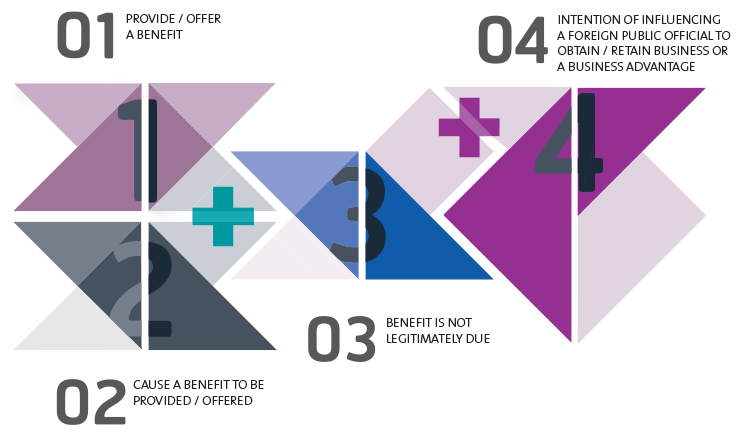

In Australia, bribing a foreign official is an offence under s 70.2 of the Schedule to the Criminal Code. The offence has the following elements:

A benefit includes any advantage and is not limited to money or other property, nor is there any formal monetary threshold. The benefit provided/offered does not need to be given directly to the relevant public official – providing or offering to provide a benefit to, for example, a family member or friend of that official would suffice. Similarly, a person who does not personally provide or offer a benefit, but instead procures someone else to do so on his or her behalf, is likely to be found to have aided, abetted, counselled or procured a bribe, which is also an offence under the Criminal Code.

It is also not necessary to prove that a benefit was actually obtained/retained. Foreign public official is also broadly defined and could include for example employees of state-owned commercial enterprises. The legislation is therefore very broad.

The following types of benefits could be captured by s 70.2 if not legitimately due and given with the intention of influencing a foreign public official to obtain or retain business or a business advantage:

The offence of bribing a foreign official will only be committed under s 70.2 if the relevant connection with Australia is established. Under s 70.5, this connection will be established if the conduct constituting the alleged offence occurs:

Where bribery is committed by a subsidiary company incorporated in a foreign jurisdiction, a joint venture vehicle or a commercial agent, the Australian parent company may still be liable in some circumstances, including where the foreign entity was acting as its agent or for aiding and abetting bribery.

The reach of the Australian legislation is wide, as are similar anti-bribery provisions in other countries, for example in the US and UK. Liability is potentially cumulative – individuals or corporations may be held liable in multiple jurisdictions under different laws for the same conduct. There is increasing cross-border cooperation between regulators/investigatory agencies to investigate and enforce anti-bribery laws.

A corporation will be liable for bribery of foreign officials by its employees, agents or officers who are found to have bribed a foreign official if that person was acting within the actual or apparent scope of their authority, and the corporation expressly, tacitly or impliedly authorised or permitted the conduct (ss 12.1-12.3). The legislation gives an expansive definition of when conduct is “expressly, tacitly or impliedly authorised or permitted”. This could include where:

Australia is also considering the introduction of a new offence of failing to prevent bribery of a foreign public official. If enacted, this offence would mean that a company is automatically liable for bribery committed by an "associate" (including a subsidiary, officer, employee, agent, contractor, or third party service provider) for the company's gain, unless the company can demonstrate that it had a proper system of internal controls and compliance in place designed to prevent the bribery from occurring.

In addition, the failure by directors or officers of a company to take proper measures to prevent and detect bribery by employees or other officers may be a breach of their duties under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The corporate regulator ASIC is taking an increasing interest in directors’ oversight of bribery and corruption risks and is starting to work with the Australian Federal Police (who have responsibility for enforcing the foreign anti-bribery laws) to investigate foreign bribery.

There are defences under the Australian law for foreign anti-bribery where:

A benefit is a facilitation payment where:

A routine government action does not include decisions about awarding new business, continuing existing business with a particular person, or the terms of a new or existing business. Similar to the US defence for facilitation payments (which the Australian defence is modelled on), the Australian legislature has made clear that a facilitation payment must involve something to which a person is already entitled and not something which the public official has a discretion whether or not to grant.

This facilitation payments defence is controversial, and the OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business Transactions has called for facilitation payments to be prohibited. Despite this recommendation, it still remains a defence under Australian law. In other jurisdictions (such as under the United Kingdom Bribery Act 2010), facilitation payments are illegal. However, the United Kingdom legislation provides a defence for commercial organisations where they prove they had adequate procedures in place.

The penalty for an individual who is found guilty of bribing a foreign official is imprisonment for not more than 10 years and/or a fine of not more than 10,000 penalty units ($2,222,000).

For a corporation, the maximum fine is the greater of:

Each State and Territory has legislation criminalising bribery of both public officials and private individuals. The Commonwealth also criminalises the bribery of Commonwealth public officials under Divisions 141 and 142 of the Criminal Code.

Each piece of legislation is different and needs to be specifically considered. However, they have a number of similar features and the following situations are likely to give rise to serious concerns:

As with foreign bribery, custom and practice are no defence, though there is generally a requirement that the benefit must be given or accepted dishonestly or corruptly. The courts have interpreted “dishonestly” or “corruptly” as meaning “with intention to influence”. So even where the legislation refers to payments which “tend to influence” (which suggests it is not necessary to have a particular intention), the need for dishonesty or corruption means that there must be an intention to influence.

While it is necessary for there to be an intention to influence, providing a benefit may be a bribe even if there is no specific objective sought to be achieved e.g. a favourable outcome of licence application or the grant of a contract; it is enough if the benefit was given to encourage the other person to show favour generally at some point in the future or act in a way which is a departure from the proper exercise of their duties.

Courts infer an intention to influence from all the circumstances in which the benefit is given e.g. the size of the benefit(s), the frequency of benefit(s), the context (e.g. if there was an impending decision regarding e.g. the grant of a licence or award of a contract), and whether the benefit was recorded by either party and recorded accurately.

In many States, paying secret commissions for advice given to others about their business dealings is also an offence, even if the adviser is not an “agent”.

Companies may be criminally liable for bribery committed by their employees, officers or agents. The Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory have adopted the expansive Commonwealth model (described above in relation to foreign bribery). In other States, corporate liability is likely to arise only where a directing mind or will of the company – typically a director or senior manager – is involved in the offence.

As with foreign bribery, companies/directors may also be liable where they aid, abet, counsel or procure bribery – that is, if they intentionally participate in the offence, for example by requiring or encouraging bribery, or providing funds to allow employees or agents to commit offences.

The penalties for domestic bribery are also heavy: prison terms ranging from up to 7 years (NSW) to up to 21 years (Tas) may be imposed on individuals, and companies are liable to significant fines.

In addition to criminal liability, all States have created statutory bodies (commissions) charged with investigating and reporting on corrupt conduct in relation to public sector agencies. The NSW Independent Commission against Corruption has conducted a number of high-profile investigations into political donations and alleged corrupt inducements over recent years, but all of the commissions are very active.

The commissions have broad powers to investigate, examine witnesses and call for documents. Hearings and reports are generally public, in the interests of transparency and public education. An investigation may also lead to a complaint being referred for criminal prosecution.

All this means that being caught up in a commission investigation imposes significant burdens on companies and individuals.

Political donations are seen as giving rise to particular risks of corruption or perceptions of corruption, and are accordingly subject to additional regulation by the Commonwealth, States and Territories. In all of the States and Territories except for Tasmania, there are requirements to file returns or make public disclosures of donations in some circumstances, with financial penalties for non-compliance. Under Commonwealth, South Australia, Queensland and Northern Territory laws, the donor (rather than the party or politician) is frequently required to file the return. NSW, Victoria and Western Australia also cap or prohibit donations above certain amounts/from certain industry sectors.

The failure to properly disclose a donation may also be evidence from which a corrupt or dishonest intention could be inferred, for the purposes of domestic bribery offences, and may be of some interest to the commissions. Accordingly, ensuring strict compliance with the disclosure rules is critical to anti-bribery risk management around political donations.

The risk of donations being seen to affect planning decisions has given rise to particular concerns. For example in NSW, political donations from property developers are unlawful. Moreover, s 10.4 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) requires a person who makes a planning application to disclose all reportable political donations under the Electoral Funding Act 2018 (NSW) made in the two years preceding the application by any person with a financial interest in the application or by the person or associate of the person making the submission.

Where contracts are entered into as a result of bribery of an agent, an innocent principal may be entitled to:

This means that the enforcement of contracts entered into following a bribe is far from certain, even if the bribe was small in nature and perhaps did not have any real impact on the principal’s entry of the contract. This is another reason why it is critical to supervise employees and agents properly: your company may find that, as a result of corrupt conduct of which it was not aware, it cannot enforce critical contracts.

In addition, contracts that have elements which relate to bribery (e.g. reimbursement of a foreign agent for their costs which might include some payments which are bribes) will be unenforceable either in whole or in part.

Australian false accounting offences target both companies and individuals, and are intended to criminalise the falsification of books, documents, records, certificates and accounts. These offences exist at both Commonwealth level (under the Commonwealth Criminal Code) and State/Territory level (pursuant to the relevant criminal legislation in each State/Territory).

For example, under s 490.1 of the Commonwealth Criminal Code, an offence occurs where:

A second offence, set out at s 490.2, applies in the same circumstances as the first, but where the person is reckless as to whether the benefit or loss would arise. In general terms, recklessness occurs where a person can foresee some probable or possible consequence, but nevertheless decides to continue with their actions with disregard to the consequences.

These false accounting offences make it much harder for companies to turn a blind eye to certain conduct and avoid prosecution. As a result, companies must ensure the process for financial reporting, invoicing and accounting is vigorous and transparent. The corporate culture must clarify that bribery and falsification of accounting documents will not be tolerated.

The Commonwealth law broadly applies to any account, record or document made or required for any accounting purposes or any register under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), or any financial report or financial record within the meaning of that Act.

This definition could capture many types of documents routinely used by most organisations, such as invoices for services or annual financial reports. The accounting documents do not need to be inside Australia and can apply to documents kept under or for the purposes of a law of the Commonwealth or kept to record the receipt or use of Australian currency.

These Commonwealth offences apply to conduct outside Australia. A 'person' includes corporate entities, government officials or an officer or employee of a corporate entity acting in the performance of their duties or functions.

In prosecuting a person for these Commonwealth false accounting offences, it is not necessary to prove that the accused received or gave a benefit, or that another person received or gave a benefit, or caused any loss to another person. Further, as mentioned above, it is also an offence to falsify documents where the person is reckless as to whether a benefit would be given or received, or loss incurred. In prosecuting this offence, it is not necessary to prove that the accused intended that a particular person receive or give a benefit, or incur a loss.

Not requiring proof that a benefit was given or received (i.e. that a bribe was paid or received) removes a difficult aspect of successful prosecution under the current bribery provisions. To establish a false accounting offence, the prosecutor is only required to show that the person intended, or was reckless in their conduct which allowed, the making, alteration, destruction or concealment of the document (or the failure to make or alter the document) to facilitate, conceal or disguise the corrupt conduct.

Companies, managers or employees who notice discrepancies in accounting documents and can foresee a probability or possibility that such discrepancy facilitates, conceals or disguises the giving or receiving a benefit that is not legitimately due, and approves the discrepancy or fails to correct that discrepancy, could fall foul of these false accounting provisions and be prosecuted.

The Commonwealth false accounting offences carry significant penalties. For an individual, an intentional breach is punishable by imprisonment for up to 10 years, a fine of up to $2,222,000 or both.

For a corporation, an intentional breach is punishable by a fine of up to $22,200,000, up to three times the value of the benefit obtained from the conduct, or up to 10% of the annual turnover of the corporation during the 12 months prior to the conduct.

The maximum term of imprisonment and pecuniary penalties for an offence of recklessness are half of the penalties for an intentional offence.

The Treasury Laws Amendment (Enhancing Whistleblower Protections) Act 2019 (Cth) has been in effect since 1 July 2019. These laws provide a consolidated, strengthened protection regime for whistleblowers for proprietary and public companies in the corporate, financial and credit sectors.

The new laws significantly expand the scope of the protected disclosures under the Corporations Act. This includes enabling whistleblowers to make anonymous disclosures, and removing the requirement that disclosures be made in "good faith".

It is important the companies and individuals are mindful of whistleblower protections, particularly confidentiality obligations, that might influence the way in which allegations of bribery and other forms of misconduct are investigated internally.

| 1. | The disclosure is made by an eligible whistleblower | An eligible whistleblower includes current or former officers, employees, contractors (including employees of contractors) and individual associates of the regulated entity or a related body corporate, or their current or former relatives or dependents, which includes a spouse or former spouse. A regulated entity includes companies, other constitutional corporations as well as the entities that are covered by the existing regimes in the banking, insurance and superannuation sectors. |

| 2. | The disclosure is made to a prescribed entity or person | The disclosure generally must be to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), a prescribed Commonwealth authority, or an "eligible recipient" such as an officer, a senior manager, an auditor, or a person authorised by the regulated entity to receive disclosures whether that be an internal or external person. Additional persons are named as an eligible recipient if the regulated entity is a superannuation entity. In particular circumstances, a protected disclosure may be made to a legal practitioner, a journalist or a parliamentarian. |

| 3. | The disclosure must be about a disclosable matter and must fall outside of the personal work-related grievance carve out | The whistleblower must have reasonable grounds to suspect the information concerns "misconduct or an improper state of affairs or circumstances". The legislation provides a non-exhaustive list of conduct that is considered a disclosable matter, which includes contraventions of certain laws administered by ASIC or APRA, offences against any other Commonwealth law that is punishable by at least 12 months' imprisonment, and conduct that represents a danger to the public or the financial system. However, this is not an exhaustive list. |

If a whistleblower's disclosure meets the requirements listed above, he/she is protected in the following ways:

The whistleblower laws require public companies and large proprietary companies (which are defined as companies that meet at least two of the following conditions: (a) $50 million or more consolidated revenue per financial year; (b) $25 million or more in assets; or (c) 100 or more employees) to maintain a compliant whistleblower policy if the business.

There are mandatory content requirements to the whistleblower policy, including information about the protections available to whistleblowers, the persons to whom disclosures may be made and how they can be made, how the company will support whistleblowers, investigate disclosures and ensure fair treatment of employees who are mentioned in protected disclosures, and how the policy will be made available to officers and employees of the company.

On 13 November 2019, ASIC issued Regulatory Guide 270 on Whistleblower Policies, which set out:

(a) the matters that must be addressed in an entity's whistleblower policy in order to be compliant;

(b) examples of content for whistleblower policies, which entities can adapt to their circumstances;

(c) some "good practice tips" which are not mandatory for entities; and (d) good practice guidance on implementing and maintaining a whistleblower policy, which is not mandatory.

The penalties for individuals and companies that breach the new whistleblower laws are as follows:

| Offence | Individuals | Companies |

| Failing to have an adequate whistleblowing policy in place (s 1317AI) | N/A |

|

| Victimisation or threatened victimisation of a whistleblower (s 1317AC) |

|

|

| Disclosing confidentiality of a whistleblower (s 1317AAE) | The penalties are the same as above. Individuals may also face up to six months imprisonment. |

As above. |

Organisations need to have in place anti-bribery policies and procedures that are proportionate to their size and the nature of their business. To design effective policies and procedures, companies need to assess the nature and extent of the risk of bribery by reference to the countries within which they transact, the types of transactions the company engages in and the parties with which the company transacts. Some risks to be aware of include:

Prevention of bribery requires an anti-corruption culture throughout the company. To develop such a culture, it must be promoted by the directors and senior executives. To be effective, anti-corruption policies and procedures require training of staff, regular communication, monitoring, and ongoing review and assessment of compliance with the policies and procedures and their effectiveness. Some practical measures include:

In 2016, the International Organisation for Standardisation released a standard (ISO 37001) to assist organisations to implement effective anti-bribery management systems. ISO 37001 is increasingly used by organisations, both in Australia and internationally. Whilst certification that your company's anti-bribery management systems comply with ISO 37001 is no guarantee that bribery issues will not arise or that your company may not still be exposed to corporate liability, certification will assist companies to demonstrate that that they have implemented an appropriate corporate culture of compliance and should not be held liable.

If officers or employees discover a problem:

Authors: James Clarke, Partner; Rani John, Partner; Alyssa Phillips, Partner; Catherine Pedler, Partner; and Dario Aloe, Lawyer.

The information provided is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to.

Readers should take legal advice before applying it to specific issues or transactions.

Sign-up to select your areas of interest

Sign-up